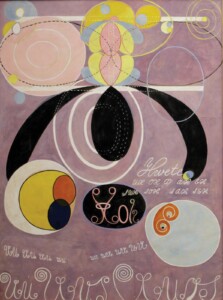

In 1907 the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint lay a three-metre piece of paper on her studio floor in Stockholm and began to paint the first of a series of abstract pictures. The result was a suite of enormous, dazzlingly beautiful paintings, made in gouache and watercolour, which she completed within the year, entitled ‘The Ten Largest’: a visual study of the four ages of man from a spiritual perspective. The first in the series, The Ten Largest, No. 1, Childhood, Group IV is as joyful as a sunny day: ecstatic flowers drift amongst untranslatable words such as ‘oo’ or ‘Vestalasket’, which tumble across the lower part of the image like psychedelic bass notes; desert-dry pinks zing against a deep-blue-sky of a background. In The Ten Largest, No. 2, Childhood, Group IV an enormous orange ball intersects with an identical dark blue one and blooms into verdant green, whilst euphoric spirals threaten to dissolve into a delirium of pale fresco blue. In The Ten Largest, No. 6, Adulthood, Group IV, invented words and the shapes of strange letters are scattered wildly across the stony pink background like a babble of cosmic graffiti. In The Ten Largest, No. 9, Old Age, Group IV, details have dissolved; infinity is intimated in dreamy, cosmic expanse of delicate, scumbled nothingness.

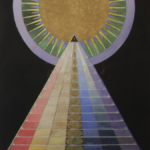

‘Hilma af Klint – A Pioneer of Abstraction’ is, without a doubt, one of the most extraordinary exhibitions I have ever seen. (It is travelling to the Hamburger Bahnof – Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin, Germany, in June, and Museo Picasso Málaga, Málaga, Spain in October.) Curated by Iris Müller-Westerman, it includes about 130 paintings and 100 works on paper, many of which are on view for the first time since the artist’s death at the age of 81. Purely minimal abstract works – for example, the ‘Parsifal’ series from 1916 – jostle with more overtly celestial and even figurative works – swans and doves and bodies mingle in an hallucinogenic celebration of eros and the spirit; a black room with the three enormous ‘Altar Pieces’ from 1915, which af Klint designed for an as-yet unbuilt temple, give Mark Rothko’s late work more than a run for its money. The staggeringly delicate and detailed ‘Tree of Knowledge’ series from 1915 segues into af Klint’s obsessive botanical drawings, such as the exquisite Violet Blossoms with Guidelines from ‘Series 1’ (1919) or Oats: A Work on Cereals from 1920. Her later work included her ‘maps’, which in 1932 appeared like premonitions of the war that was to engulf the world: in A Map: Great Britain (1932), for example, a head, positioned over Europe, spews dark flames towards the UK.

Af Klint was born in 1862; in 1879 she began participating in séances and in 1880 her sister died, a tragedy that encouraged the artist’s interest in religion and spirituality. By1896, however, af Klint, who had been a star pupil at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, decided to reject the depiction of external reality in her paintings and started practicing automatic writing – roughly 30 years before the surrealists. She became closely involved with a group of four women, all of whom were interested in spirituality, automatic writing and drawing, and were influenced by theosophy and the teachings of Rudolf Steiner; they called themselves ‘The Five’ and continued to meet for the rest of their lives. In 1904, during a séance, af Klint was told by a spirit guide, Amaliel, that she had been ‘commissioned’ to make paintings on the astral plane. Between 1906–8 she painted the first 111 paintings that comprised the beginning of the series, ‘The Paintings of the Temple’; she stopped for four years to look after her mother, before creating another 82 paintings between 1912–15, thus completing the commission. In the comprehensive exhibition catalogue, Müller-Westerman quotes af Klint describing her working process: ‘The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless, I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brushstroke.’

The story of af Klint’s life and work is not simply the tale of an extraordinary woman, but a study in how traditional art history has been written: bluntly put, a reflection of the market, by men. In 1970, Pontus Hultén, the then-Director of the Moderna Museet, was offered the entire af Klint estate but turned it down, apparently dismissing her work because of its relationship to spiritualism. Similarly, af Klint was not even a footnote in the recent show at MoMA New York, ‘Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925’: the show’s curator, Leah Dickerman, justified the artist’s exclusion because she is not convinced that af Klint’s paintings are art. This is absurd. Af Klint was trained at an art school and was deeply involved in the artistic debates of the day. It’s hard not to feel she has been excluded because of her spiritualism, and the fact that her work is in no major collections: in her will, af Klint stipulated that it could not be sold, although individual works can be released to support the upkeep of the collection, and only then, to an institution (this has not yet happened). Yet Kandinsky, Mondrian and Malevich, all stars of the MoMA show – and, it must be noted, part of its collection – drank deeply from the same spiritual sources as af Klint. (A quote from Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art from 1911 is apt here: ‘The true work of art is born from the Artist: a mysterious, enigmatic, and mystical creation.’) However, thankfully, there have been curators who have supported af Klint’s work: in 1983, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, curator Maurice Tuchman included 16 of her paintings in his landmark exhibition, ‘The Spiritual in Art’; and in 2006, London’s Camden Art Centre held the first exhibition of her works in the UK, titled ‘An Atom in the Universe’.

In 1944, af Klint died after a fall (curiously, it was the same year Mondrian, Malevich and Kandinsky also died). In her will, she left more than 1,000 paintings, watercolours and drawings, and 27,000 pages of notebooks – which the Moderna Museet is in the process of digitizing – to her nephew, Erik af Klint; it is now owned by a foundation run by her family. She also stipulated that her work could not be shown publicly until 20 years after her death; she believed that the world was not ready to understand the significance of her visions. Hopefully, it is now.