The search for otherness is a commonplace in modern art. If, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, European artists traveled to the Americas, Africa, the East and Oceania, financed by the colonizing power, the problem takes on new contours in the 21st century. Today, it is the artist of great urban centers’ middle classes who works with historically oppressed populations and goes in search of remote experiences. The debate about these approaches and the implications of the different “speaking places” involved in these actions are on today’s agenda, both in the art field and in the social field. In the Amazon, a territory of violence against indigenous populations since the colonial period, this debate takes on a different problem layer, that of “cultural extractivism.” Frederico Filippi and Maya Da-Rin are artists who deal with these flows between city and forest, giving visibility to the economic, cultural and subjective contradictions resulting from those processes.

Frederico Filippi: The artist as an informant

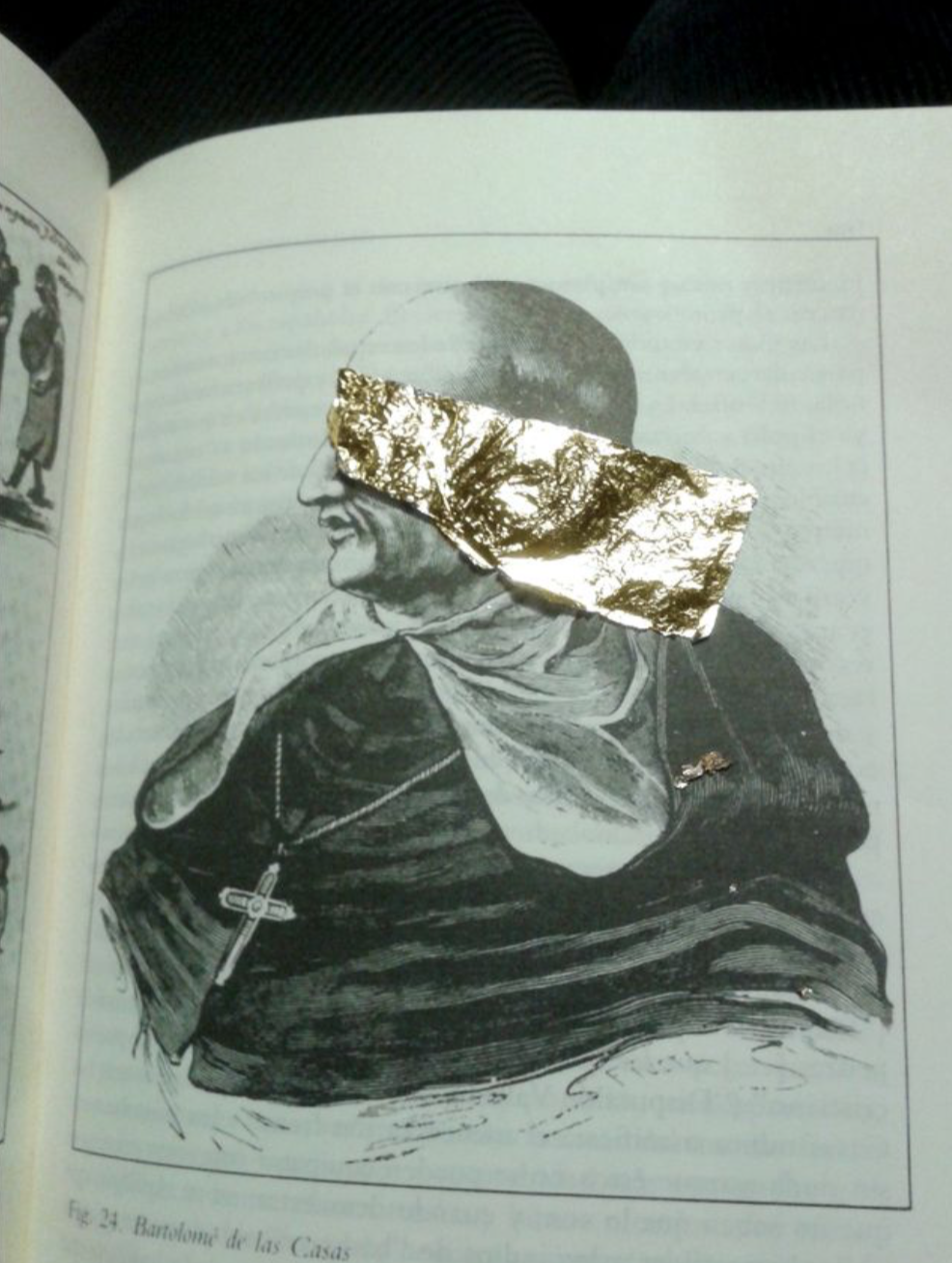

It was in a residence at Matadero Madrid that Frederico Filippi structured an artistic research that would reach the Amazon years later. In Spain, he developed a trilogy of works using the metals that guided the invasions of the Americas – gold, silver and bronze. In an action against the methods used by the European conquerors over the invaded territories, he chose as a strategy the appropriation and clandestine, unauthorized infiltration of monuments, commemorative spaces and documentation centers. “Direito de Resposta” (Right to Answer, 2014) is the title of interventions directly carried out on the matrices of the “discovery” official discourses, in the Spanish capital.

Gold returned to the artist’s research in the series Seivas (Saps, 2020), composed of paintings of the words gold, mercury and fire – elements that modify the landscape and the environment –, put in circulation on trucks. The work took place on the road. A metal used in the purification of illegally extracted gold in the Amazon, mercury is the element that also reports the artist’s activity as an informant.

In a series of texts about the challenges of a traveling artist, the Belgian critic and historian Marcus Verhagen discusses art’s temporality in a globalized world. Acceleration being the norm, he argues that its intensification turns out to be a way of solving the intrinsic inequities of this system and deceleration is pointed as a conservative, sometimes escapist and alienated way out. Therefore, it is worth thinking about how traveling artists make their displacements, without imposing their speed or temporality as a “bourgeois subject.”

By choosing the road as a field of action, Filippi refers both to the globalized world dynamics and to a specific period of Amazonian history: colonization through the national-developmentalist project of the Brazilian military dictatorship. Roads are gaps in the forest that gave access to looting, diseases and contamination. The feeling of revenge and reparation can be seen as the driving power behind his research of “frontier materials”, such as rubber and the bodies of abandoned vehicles, civilization’s garbage piled up in the interstices between forests and devastated areas. It is on the margins that the artist deepens his research on the arc of deforestation, providing information on how economic and developmental cycles have influenced the landscape’s geophysical transformation.

In the series “Carne de Caça” (Game Meat, 2019), Frederico Filippi paints on fragments of burned cars. The contrast between the paintings made with melted asphalt, generating an uncertain geometry, and the burnt carcasses – frontier material – configure the temporal shock pointed out by Verhagen. These industrial objects, which assume the condition of archaeological residues of extractive times and actions, produce a shuffling between present, past and future. “I was always impacted by the patterns and repetitions not only in indigenous paintings, but also in cave paintings. There is a certain trance in the repetition of an image”, Filippi tells seLecT.

Maya Da-Rin: moving frontiers

Drift and observation are inherent conditions in all of the filmic and installation work of artist Maya Da-Rin. Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1979, graduated from Le Fresnoy – Studio National des Arts Contemporains, in Tourcoing, France, and with a master’s degree in Cinema and Art History at the Sorbonne Nouvelle, Paris, the filmmaker and artist has the transit in her own education.

From “Margens” (Margins, 2007), filmed from the mobile point of view of a vessel slowly navigating the Amazon River, to “A Febre” (Fever, 2019), the first fictional feature, through “Terras” (Lands, 2009), “Horizonte de Eventos” (Events’ Horizon, 2012) and “Camuflagem” (Camouflage, 2013), “the works are born from each other”, succeeding like the waters of a river and forming a hydrographic network.

The issue of temporalities involved in relational processes can also be assessed here, since in “Margens” the boat speed determines the film speed. The camera never leaves the boat and the narrators are the travelers who board and disembark during the two days and three nights of a journey that departs from the border between Brazil and Colombia, towards the Peruvian city of Iquitos. On the trip, Da-Rin met Basilia, a native of the Bora ethnic group, born in Letícia, Colombia. One of her daughters was a nursing technician. From the conversation with Basilia, the character Vanessa was born, from the feature-film A Febre. Nurse Vanessa is Justino’s youngest daughter, the indigenous Desana who stars in the film. “It was from this meeting that the desire to make a fiction film about an indigenous family that had migrated to the city was born. I decided to do it in Manaus, a large industrial center in the middle of the forest,” says the artist to seLecT.

Between observation and surveillance

Thematizing an indigenous person living on the outskirts of Manaus signals the artist’s interest in social groups that suffer in transits between the forest and the city. The melancholy scenes of long bus rides home or solitary night work are recurrent. That Justino works as a night guard in a cargo port, in surveillance of a place of entry and exit of goods that he does not know, also indicates a criticism of the globalization processes. The contrast between the indigenous cosmogonic imagination and their automated work routine indicates that their inexplicable fever is the symptom of a serious civilizational maladjustment.

The focus on the interstices between civilization and forest is also revealed in the dynamics between the three languages spoken: Portuguese, Tikuna and Tukano, a lingua franca among indigenous peoples of Rio Negro, spoken in urban villages formed since the 18th century, on account of the catechizing processes. “In the coming and going of languages, it’s not just words that change, but times, pauses, corporal gestures. There is a whole cultural system that is activated with a language,” says Da-Rin.

Fever starts from the same drifting process, from previous documentary works. The script is the result of collective dynamics with the cast of indigenous people, triggering a correspondence between the documentary and fictional processes of reality construction. The artist claims that the use of fiction enabled her to freely describe the protagonist’s dream and inner experience, given the inexistence of boundaries between the real and the imaginary, typical of indigenous peoples’ knowledge system. “The text is not decorated, but incorporated, it is knowledge that is stored in the body and not on paper,” she says.

If listening and observing are procedures of the traveling artist, it is surveillance that imposes itself as a fundamental issue in Fever. During the night, Justino is chased by a mysterious creature and, during the day, has his job watched. We can take this character’s condition as the author’s self-reflection on the film’s own “speaking place” and on its power – panoptic or relational – to produce and disseminate images about other contexts.